Welcome to Shanshan Blog!

-

Google Code Jam Qualification Round 2016 B. Revenge of the Pancakes

Problem

The Infinite House of Pancakes has just introduced a new kind of pancake! It has a happy face made of chocolate chips on one side (the “happy side”), and nothing on the other side (the “blank side”).

You are the head waiter on duty, and the kitchen has just given you a stack of pancakes to serve to a customer. Like any good pancake server, you have X-ray pancake vision, and you can see whether each pancake in the stack has the happy side up or the blank side up. You think the customer will be happiest if every pancake is happy side up when you serve them.

You know the following maneuver: carefully lift up some number of pancakes (possibly all of them) from the top of the stack, flip that entire group over, and then put the group back down on top of any pancakes that you did not lift up. When flipping a group of pancakes, you flip the entire group in one motion; you do not individually flip each pancake. Formally: if we number the pancakes 1, 2, …, N from top to bottom, you choose the top i pancakes to flip. Then, after the flip, the stack is i, i-1, …, 2, 1, i+1, i+2, …, N. Pancakes 1, 2, …, i now have the opposite side up, whereas pancakes i+1, i+2, …, N have the same side up that they had up before.

For example, let’s denote the happy side as + and the blank side as -. Suppose that the stack, starting from the top, is –+-. One valid way to execute the maneuver would be to pick up the top three, flip the entire group, and put them back down on the remaining fourth pancake (which would stay where it is and remain unchanged). The new state of the stack would then be -++-. The other valid ways would be to pick up and flip the top one, the top two, or all four. It would not be valid to choose and flip the middle two or the bottom one, for example; you can only take some number off the top.

You will not serve the customer until every pancake is happy side up, but you don’t want the pancakes to get cold, so you have to act fast! What is the smallest number of times you will need to execute the maneuver to get all the pancakes happy side up, if you make optimal choices?

Input and Output

Input

The first line of the input gives the number of test cases, T. T test cases follow. Each consists of one line with a string S, each character of which is either + (which represents a pancake that is initially happy side up) or - (which represents a pancake that is initially blank side up). The string, when read left to right, represents the stack when viewed from top to bottom.

Output

For each test case, output one line containing Case #x: y, where x is the test case number (starting from 1) and y is the minimum number of times you will need to execute the maneuver to get all the pancakes happy side up.

Limits

1 ≤ T ≤ 100.

Every character in S is either + or -.

Small dataset

1 ≤ length of S ≤ 10.

Large dataset

1 ≤ length of S ≤ 100.

Sample

Input 5 - -+ +- +++ --+- Output Case #1: 1 Case #2: 1 Case #3: 2 Case #4: 0 Case #5: 3In Case #1, you only need to execute the maneuver once, flipping the first (and only) pancake.

In Case #2, you only need to execute the maneuver once, flipping only the first pancake.

In Case #3, you must execute the maneuver twice. One optimal solution is to flip only the first pancake, changing the stack to –, and then flip both pancakes, changing the stack to ++. Notice that you cannot just flip the bottom pancake individually to get a one-move solution; every time you execute the maneuver, you must select a stack starting from the top.

In Case #4, all of the pancakes are already happy side up, so there is no need to do anything.

In Case #5, one valid solution is to first flip the entire stack of pancakes to get +-++, then flip the top pancake to get –++, then finally flip the top two pancakes to get ++++.

Codes

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int dp[101]; int main() { freopen("C:\\Users\\Administrator\\Downloads\\B-small-practice.in","r",stdin); freopen("C:\\Users\\Administrator\\Downloads\\B-small-attempt0.out","w",stdout); int num; cin >> num; string s; for (int i=0; i<num; i++) { cin >> s; cout << "Case #" << i+1 << ": "; if (s[0]=='+') dp[0] = 0; else dp[0] = 1; for (int i =1; i<s.size(); i++) { if (s[i] == s[i-1] || ((s[i]=='+')&&(s[i-1]=='-'))) dp[i] = dp[i-1]; else dp[i] = dp[i-1] + 2; } cout << dp[s.size()-1] << endl; } return 0; }

-

Google Code Jam Qualification Round 2016 A.Counting Sheep

Problem

Bleatrix Trotter the sheep has devised a strategy that helps her fall asleep faster. First, she picks a number N. Then she starts naming N, 2 × N, 3 × N, and so on. Whenever she names a number, she thinks about all of the digits in that number. She keeps track of which digits (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) she has seen at least once so far as part of any number she has named. Once she has seen each of the ten digits at least once, she will fall asleep.

Bleatrix must start with N and must always name (i + 1) × N directly after i × N. For example, suppose that Bleatrix picks N = 1692. She would count as follows:

N = 1692. Now she has seen the digits 1, 2, 6, and 9. 2N = 3384. Now she has seen the digits 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9. 3N = 5076. Now she has seen all ten digits, and falls asleep. What is the last number that she will name before falling asleep? If she will count forever, print INSOMNIA instead.

Input and Output

Input

The first line of the input gives the number of test cases, T. T test cases follow. Each consists of one line with a single integer N, the number Bleatrix has chosen.

Output

For each test case, output one line containing Case #x: y, where x is the test case number (starting from 1) and y is the last number that Bleatrix will name before falling asleep, according to the rules described in the statement.

Limits

1 ≤ T ≤ 100.

Small dataset

0 ≤ N ≤ 200.

Large dataset

0 ≤ N ≤ 106.

Sample

Input 5 0 1 2 11 1692 Output Case #1: INSOMNIA Case #2: 10 Case #3: 90 Case #4: 110 Case #5: 5076In Case #1, since 2 × 0 = 0, 3 × 0 = 0, and so on, Bleatrix will never see any digit other than 0, and so she will count forever and never fall asleep. Poor sheep!

In Case #2, Bleatrix will name 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. The 0 will be the last digit needed, and so she will fall asleep after 10.

In Case #3, Bleatrix will name 2, 4, 6… and so on. She will not see the digit 9 in any number until 90, at which point she will fall asleep. By that point, she will have already seen the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, which will have appeared for the first time in the numbers 10, 10, 2, 30, 4, 50, 6, 70, and 8, respectively.

In Case #4, Bleatrix will name 11, 22, 33, 44, 55, 66, 77, 88, 99, 110 and then fall asleep.

Case #5 is the one described in the problem statement. Note that it would only show up in the Large dataset, and not in the Small dataset.

Codes

#include <iostream> using namespace std; int main() { freopen("C:\\Users\\Administrator\\Downloads\\A-large-practice.in","r",stdin); freopen("C:\\Users\\Administrator\\Downloads\\A-large-attempt0.out","w",stdout); int num, m; cin >> num; for (int i=0; i<num; i++) { cin >> m; cout << "Case #" << i+1 << ": "; if ( m==0 ) cout << "INSOMNIA" << endl; else { int n = 0; int x; for (x = m; n < (1 << 10) - 1; x += m) { int y = x; while (y) { n |= 1 << (y % 10); y /= 10; } } cout << x-m << endl; } } return 0; }

-

Leetcode (75) Sort Series

Leetcode Sort Series

Leetcode 75. Sort Colors

Given an array with n objects colored red, white or blue, sort them so that objects of the same color are adjacent, with the colors in the order red, white and blue.

Here, we will use the integers 0, 1, and 2 to represent the color red, white, and blue respectively.

class Solution { public: void sortColors(vector<int>& nums) { int zero=0, two=nums.size()-1; for (int i=0; i<=two;) { if (nums[i]==0) swap(nums[i++], nums[zero++]); else if (nums[i]==2) swap(nums[i], nums[two--]); else i++; } } };

-

Leetcode (77, 79) DFS Series

Leetcode DFS Series

Leetcode 77. Combinations

Given two integers n and k, return all possible combinations of k numbers out of 1 … n.

For example, If n = 4 and k = 2, a solution is:

[ [2,4], [3,4], [2,3], [1,2], [1,3], [1,4], ]class Solution { public: vector<vector<int>> combine(int n, int k) { vector<vector<int>> res; vector<int> curr; if (n<k) return res; helper(res, curr, 1, n, k); return res; } void helper(vector<vector<int>> &res, vector<int> &curr, int pos, int n, int k) { if (k==0){ res.push_back(curr); return; } for (int i=pos; i<=n; i++) { curr.push_back(i); helper(res, curr, i+1, n, k-1); curr.pop_back(); } } };Leetcode 79. Word Search

Given a 2D board and a word, find if the word exists in the grid.

The word can be constructed from letters of sequentially adjacent cell, where “adjacent” cells are those horizontally or vertically neighboring. The same letter cell may not be used more than once.

For example, Given board =

[ ['A','B','C','E'], ['S','F','C','S'], ['A','D','E','E'] ]word = “ABCCED”, -> returns

true,word = “SEE”, -> returns

true,word = “ABCB”, -> returns

false.class Solution { public: bool exist(vector<vector<char>>& board, string word) { if (board.empty() || word.empty()) return false; const int m = board.size(); const int n = board[0].size(); for (int i=0; i<m; i++) for (int j=0; j<n; j++) if (board[i][j]==word[0]) if (helper(board, word, i, j, 0, m, n)) return true; return false; } bool helper(vector<vector<char>> &board, string word, int i, int j, int pos, int m, int n) { if (pos==word.size()) return true; if (i<0 || j<0 || i>=m || j>=n || board[i][j]=='@' || board[i][j]!=word[pos]) return false; char temp = board[i][j]; board[i][j] = '@'; if (helper(board, word, i-1, j, pos+1, m, n) || helper(board, word, i+1, j, pos+1, m, n) || helper(board, word, i, j-1, pos+1, m, n) | helper(board, word, i, j+1, pos+1, m, n)) return true; board[i][j] = temp; return false; } };

-

500 Lines or Less Chapter 7: DBDB: Dog Bed Database 翻译

介绍

DBDB(Dog Bed Database)是一个实现简单的键/值数据库的Python库。它允许你将键与值关联,并将其存储在磁盘上以供稍后检索。

DBDB旨在保护数据在面临计算机崩溃和错误条件,避免将所有数据保存在RAM中,因此你可以存储比RAM多的数据。

内存

我记得我第一次卡在一个bug。当我写完我的基础程序并运行它,奇怪的闪光像素出现在屏幕上,程序提前中止。当我回看代码时,最后几行代码消失了。

我妈妈的一个朋友知道如何编程,所以我们打了个电话。在与她谈话的几分钟内,我发现了问题:程序太大,侵犯到了视频内存。清除屏幕截断程序,闪烁是Applesoft BASIC在程序结束之后将程序状态存储在RAM中的行为的工件。

从此我非常关心内存分配。我学习了指针和如何使用malloc分配内存,数据结构是如何在内存中布局。我学会了非常,非常小心地改变它们。

几年后,在阅读Erlang的面向过程的语言时,我发现它实际上不需要复制数据来在进程之间发送消息,因为一切都是不可变的。然后我在Clojure中发现了不可变的数据结构。

2013年当我阅读CouchDB的时候,我只是微笑和点头,认识到管理复杂数据的结构和机制,因为它会改变。

我学会了你可以设计围绕不可变数据构建的系统。

然后我同意为这本书写一章节。

我想,描述CouchDB的核心数据存储概念将是有趣的。

在试图写一个二叉树算法来改变树的地方,我很沮丧事情变得复杂。边缘案例的数量,并试图解释树一部分的变化如何影响其他人,让我很是头痛。我不知道我将如何解释这一切。

记住经验教训,我看了一个递归算法更新不可变二叉树,结果是相对而直接。

我再次学到,更容易推理不可变的事情。

为什么是有趣的

大多数项目需要某种数据库。你需要自己写;有许多边缘情况会打击你,即使你只是写JSON到磁盘:

-

如果文件系统空间不足,会发生什么?

-

如果您的笔记本电脑在保存时会死机怎么办?

-

如果您的数据大小超过可用内存会怎么样?(不适用于现代台式机上的大多数应用程序,但不大可能用于移动设备或服务器端Web应用程序)。

然而,如果你想了解数据库如何处理所有这些问题,自己写一个可能会更好。

我们在这里讨论的技术和概念适用于需要在面对失败时具有理性的,可预测的行为的任何问题。

说到失败…

表征故障

数据库的特征通常在于它们紧密地符合ACID属性:原子性,一致性,隔离和持久性。

DBDB中的更新是原子性和持久性的,两个属性将在本章后面描述。 DBDB不提供一致性保证,因为对存储的数据没有约束。同样不实现隔离。

应用程序代码当然可以加强一致性保证,但适当的隔离需要事务管理器。我们不在这里尝试;但是,您可以在CircleDB一章中了解有关事务管理的更多信息。

我们还有其他系统维护问题需要考虑。在此实现中不会回收陈旧的数据,因此重复更新(即使是相同的密钥)将最终占用所有磁盘空间。 (你会很快发现为什么会是这种情况。)PostgreSQL调用这个回收“真空”(使旧行空间可供重用),CouchDB称之为“压缩”(通过重写数据的“活”部分到一个新文件,并原子地移动它在旧的文件)。

可以添加压缩功能增强DBDB,但是这个问题留给读者练习。

DBDB的架构

DBDB将数据的逻辑结构(在本例中为二叉树;逻辑层)中的“放在磁盘上的某处”(如何将数据布置在文件中;物理层)的关注从键/值存储(将键

a与值foo关联;公共API)。许多数据库将逻辑和物理方面分开,因为提供的可选实现方式通常是有用的,以获得不同的性能特性,例如, DB2的SMS(文件系统中的文件)与DMS(原始块设备)表空间或MySQL的替代引擎实现。

探索设计

本书中的大部分章节描述了一个程序是如何从开始到完成的。然而,这不是我们与开发的代码进行的交互。我们经常看别人写的代码,并找出如何修改或扩展它来做不同的事情。

在本章中,我们假设DBDB是一个完整的项目,并通过它来了解它是如何工作的。首先,让我们来探索整个项目的结构。

组织单位

单位按距离最终用户的距离排序;也就是说,第一个模块是这个程序的用户可能需要知道的最多的模块,而最后一个模块只有很少的交互。

-

tool.py定义了用于从终端窗口探索数据库的命令行工具。 -

interface.py定义了实现Python字典API的类(DBDB),它使用的是BinaryTree。这是你如何在Python程序中使用DBDB。 -

logical.py定义逻辑层。它是一个键/值存储的抽象接口。

**

LogicalBase提供了用于逻辑更新(如get,set和commit)的API和用一个具体的子类来实现更新本身。它还管理存储锁定和解除引用内部节点。**

ValueRef是一个Python对象,它引用存储在数据库中的二进制blob。间接允许我们避免将整个数据存储一次性加载到内存中。binary_tree.py在逻辑接口下定义了一个具体的二叉树算法。

**

BinaryTree提供了一个二叉树的具体实现,包括获取,插入和删除键/值的方法。BinaryTree表示不可变树;通过返回与旧的树共享共同结构的新树来执行更新。**

BinaryNode实现二叉树的一个节点。** ·BinaryNodeRef·是一个专门的

ValueRef,它知道如何序列化和反序列化一个BinaryNode。physical.py定义物理层。Storage类提供持久的(大多数)仅追加记录存储。

这些模块从试图给每个类一个单一的责任。换句话说,每个类都只有一个改变的理由。

读取值

我们将从最简单的情况开始:从数据库读取值。当我们尝试在

example.db中获取与键foo关联的值时会发生什么:$ python -m dbdb.tool example.db get foo这运行了模块

dbdb.tool里的main()函数:# dbdb/tool.py def main(argv): if not (4 <= len(argv) <= 5): usage() return BAD_ARGS dbname, verb, key, value = (argv[1:] + [None])[:4] if verb not in {'get', 'set', 'delete'}: usage() return BAD_VERB db = dbdb.connect(dbname) # CONNECT try: if verb == 'get': sys.stdout.write(db[key]) # GET VALUE elif verb == 'set': db[key] = value db.commit() else: del db[key] db.commit() except KeyError: print("Key not found", file=sys.stderr) return BAD_KEY return OKconnect()函数打开数据库文件(可能创建,但不会覆盖它),并返回DBDB的实例:# dbdb/__init__.py def connect(dbname): try: f = open(dbname, 'r+b') except IOError: fd = os.open(dbname, os.O_RDWR | os.O_CREAT) f = os.fdopen(fd, 'r+b') return DBDB(f)# dbdb/interface.py class DBDB(object): def __init__(self, f): self._storage = Storage(f) self._tree = BinaryTree(self._storage)DBDB有一个对

Storage的实例的引用,但它也与self._tree共享该引用。 为什么? 不能self._tree管理对存储本身的访问?在设计中哪些对象“拥有”资源是一个重要的问题,因为它给我们提示的变化可能是不安全的。 让我们继续跟进这个问题。

一旦我们有一个DBDB实例,通过字典查找(

db [key])获得key的值,这将导致Python解释器调用DBDB .__ getitem __()。# dbdb/interface.py class DBDB(object): # ... def __getitem__(self, key): self._assert_not_closed() return self._tree.get(key) def _assert_not_closed(self): if self._storage.closed: raise ValueError('Database closed.')__getitem __()通过调用_assert_not_closed确保数据库仍处于打开状态。这里我们看到至少一个原因为什么DBDB需要直接访问我们的存储实例:所以它是强制执行的前提条件。 (你同意这个设计吗?或者你想出一种不同的方式,我们可以这样做吗?)DBDB然后通过调用

_tree.get()(由LogicalBase提供)检索与内部_tree的键相关联的值:# dbdb/logical.py class LogicalBase(object): # ... def get(self, key): if not self._storage.locked: self._refresh_tree_ref() return self._get(self._follow(self._tree_ref), key)get()检查我们是否锁定了存储。我们不是100%肯定为什么可能有锁在这里,但我们可以猜测,它可能存在,允许writer序列化访问数据。 如果存储未锁定,会发生什么?# dbdb/logical.py class LogicalBase(object): # ... def _refresh_tree_ref(self): self._tree_ref = self.node_ref_class( address=self._storage.get_root_address())_refresh_tree_ref将树的“视图”重置为当前磁盘上的数据,从而允许我们执行最新的读取。如果我们尝试读取时存储被锁定怎么办? 这意味着其他一些进程可能正在改变我们现在想要读取的数据; 我们读取的不是最新的数据的当前状态。这通常被称为“脏读”。这种模式允许许多reader访问数据,而不必担心阻塞。

现在,让我们来看看实际如何检索数据:

# dbdb/binary_tree.py class BinaryTree(LogicalBase): # ... def _get(self, node, key): while node is not None: if key < node.key: node = self._follow(node.left_ref) elif node.key < key: node = self._follow(node.right_ref) else: return self._follow(node.value_ref) raise KeyError这是一个标准的二叉树搜索,指向它们的节点。 我们从

BinaryTree文档中知道Nodes和NodeRefs是值对象:它们是不可变的,它们的内容从不改变。使用关联的键和值以及左和右子节点创建节点。 这些关联也从不改变。 当根节点被替换时,整个BinaryTree的内容仅可见地改变。 这意味着我们不需要担心在我们执行搜索时树的内容被更改。一旦找到相关的值,它被

main()写入stdout,而不添加任何额外的换行符,以保留用户的数据。插入和更新

现在我们在

example.db中将键foo设置为value bar:$ python -m dbdb.tool example.db set foo bar再次运行模块

dbdb.tool里的main()函数。在我们看代码之前,我们先强调一下这个重要的部分:# dbdb/tool.py def main(argv): ... db = dbdb.connect(dbname) # CONNECT try: ... elif verb == 'set': db[key] = value # SET VALUE db.commit() # COMMIT ... except KeyError: ...这里我们设置

db[key] = value的值调用DBDB.__setitem__().# dbdb/interface.py class DBDB(object): # ... def __setitem__(self, key, value): self._assert_not_closed() return self._tree.set(key, value)__setitem__确保数据库仍然处于打开状态,然后通过调用_tree.set()将关联从键值传递到内部_tree。_tree.set()由LogicalBase提供:# dbdb/logical.py class LogicalBase(object): # ... def set(self, key, value): if self._storage.lock(): self._refresh_tree_ref() self._tree_ref = self._insert( self._follow(self._tree_ref), key, self.value_ref_class(value))set()第一次检查存储锁:# dbdb/storage.py class Storage(object): ... def lock(self): if not self.locked: portalocker.lock(self._f, portalocker.LOCK_EX) self.locked = True return True else: return False这里有两个重要的事情需要注意:

-

我们的锁由一个第三方文件锁库portalocker提供。

-

如果数据库已经被锁定,

lock()返回False,否则返回True。

回到

_tree.set(),我们现在可以理解为什么它首先检查lock()的返回值:它允许我们为最近的根节点引用调用_refresh_tree_ref,所以我们不会丢失另一个进程的更新。然后,它用包含插入(或更新)的键/值的新树替换根树节点。插入或更新树不会改变任何节点,因为

_insert()返回一个新的树。新树与前一个树共享未更改的部分,以节省内存和执行时间。 自然地递归实现:# dbdb/binary_tree.py class BinaryTree(LogicalBase): # ... def _insert(self, node, key, value_ref): if node is None: new_node = BinaryNode( self.node_ref_class(), key, value_ref, self.node_ref_class(), 1) elif key < node.key: new_node = BinaryNode.from_node( node, left_ref=self._insert( self._follow(node.left_ref), key, value_ref)) elif node.key < key: new_node = BinaryNode.from_node( node, right_ref=self._insert( self._follow(node.right_ref), key, value_ref)) else: new_node = BinaryNode.from_node(node, value_ref=value_ref) return self.node_ref_class(referent=new_node)注意我们如何总是返回一个新的节点(包裹在

NodeRef中)。 不是更新一个节点来指向一个新的子树,而是创建一个共享未改变的子树的新节点。 这是什么使这个二叉树是一个不可变的数据结构。你可能注意到了一些奇怪的事情:我们还没有对磁盘上的任何东西进行任何更改。 我们所做的是通过移动树节点来操纵我们对磁盘数据的视图。

为了将这些更改实际写入磁盘,我们需要显式调用

commit(),我们在本节开头的tool.py中的是set操作的第二部分。提交包括写出内存中的所有脏状态,然后保存树的新根节点的磁盘地址。

从API开始:

# dbdb/interface.py class DBDB(object): # ... def commit(self): self._assert_not_closed() self._tree.commit()_tree.commit()来自LogicalBase:# dbdb/logical.py class LogicalBase(object) # ... def commit(self): self._tree_ref.store(self._storage) self._storage.commit_root_address(self._tree_ref.address)所有

NodeRefs都知道如何通过prepare_to_store()让他们的子进程序列化来将其串行到磁盘:# dbdb/logical.py class ValueRef(object): # ... def store(self, storage): if self._referent is not None and not self._address: self.prepare_to_store(storage) self._address = storage.write(self.referent_to_string(self._referent))LogicalBase离得

self._tree_ref实际上是一个二进制NodeRef(ValueRef的子类),所以prepare_to_store()的具体实现是:# dbdb/binary_tree.py class BinaryNodeRef(ValueRef): def prepare_to_store(self, storage): if self._referent: self._referent.store_refs(storage)问题里的BinaryNode,

_referent,其引用存储自己:# dbdb/binary_tree.py class BinaryNode(object): # ... def store_refs(self, storage): self.value_ref.store(storage) self.left_ref.store(storage) self.right_ref.store(storage)这对于未写入的更改的

NodeRef(即,没有_address),一直向下递归。现在我们再次在

ValueRef的store方法中备份栈。store()的最后一步是序列化此节点并保存其存储地址:# dbdb/logical.py class ValueRef(object): # ... def store(self, storage): if self._referent is not None and not self._address: self.prepare_to_store(storage) self._address = storage.write(self.referent_to_string(self._referent))在这一点上,

NodeRef的_referent保证有可用于它自己的所有refs的地址,所以我们通过创建表示这个节点的bytestring来序列化它:# dbdb/binary_tree.py class BinaryNodeRef(ValueRef): # ... @staticmethod def referent_to_string(referent): return pickle.dumps({ 'left': referent.left_ref.address, 'key': referent.key, 'value': referent.value_ref.address, 'right': referent.right_ref.address, 'length': referent.length, })更新

store()方法中的地址技术上是ValueRef的一个突变。 因为它对用户可见的值没有影响,所以可以认为它是不可变的。一旦在根

_tree_ref上的store()完成(在LogicalBase.commit()),我们知道所有的数据都写入磁盘。现在我们可以通过调用提交根地址:# dbdb/physical.py class Storage(object): # ... def commit_root_address(self, root_address): self.lock() self._f.flush() self._seek_superblock() self._write_integer(root_address) self._f.flush() self.unlock()刷新文件(以便操作系统知道我们希望所有的数据保存到稳定的存储,如SSD),并写出根节点的地址。我们知道最后一个写是原子的,因为我们将磁盘地址存储在扇区边界上。这是第一件要做的事,因此无论扇区大小如何,单扇区磁盘写入保证是由磁盘硬件原子。

因为根节点地址具有旧值或新值,其他进程可以从数据库读取而不获取锁。外部进程可能会看到旧的或新的树,但不会混合两者。所以,提交是原子的。

因为我们在写入根节点地址之前将新数据写入磁盘并调用

fsync syscall,所以未提交的数据不可访问。相反的,一旦根节点地址被更新,我们知道它引用的所有数据也在磁盘上。所以,提交是持久的。这样就完成了!

NodeRefs如何保存内存

为了避免在存储器中同时保持整个树结构,当从磁盘读入逻辑节点时,将其左右孩子的磁盘地址(及其值)加载到存储器中。访问孩子及其值需要一个额外的函数调用

NodeRef.get()取消引用数据。我们需要构造的一个

NodeRef是一个地址:+---------+ | NodeRef | | ------- | | addr=3 | | get() | +---------+调用

get()将返回具体的节点,以及该节点的引用NodeRefs:+---------+ +---------+ +---------+ | NodeRef | | Node | | NodeRef | | ------- | | ------- | +-> | ------- | | addr=3 | | key=A | | | addr=1 | | get() ------> | value=B | | +---------+ +---------+ | left ----+ | right ----+ +---------+ +---------+ | | NodeRef | +-> | ------- | | addr=2 | +---------+当未提交对树的更改时,它们存在于内存中,从根到引用到更改的树叶。更改尚未保存到磁盘,因此更改的节点包含具体的键和值,并且没有磁盘地址。进行写操作的进程可以看到未提交的更改,并且可以在发出提交之前进行更改,因为如果

NodeRef.get()有一个提交,它将返回未提交的值;当通过API访问时,提交和未提交数据之间没有区别。所有更新将原子地显示给其他读者,因为更改在新的根节点地址写入磁盘之前不可见。并发更新被磁盘上的lockfile阻止。锁在第一次更新时获取,并在提交后释放。读者的练习

DBDB允许许多进程同时读取同一个数据库而不阻塞,但读者有时可以检索旧数据。如果我们需要一致地读取一些数据怎么办?一个常见的用例是读取一个值,然后根据该值更新它。你将如何在DBDB来实现这一点?

用于更新数据存储的算法可以通过替换

interface.py中的字符串BinaryTree完全改变。数据存储趋向于使用更复杂的搜索树,例如B树,B+树等,以提高性能。虽然一个平衡的二叉树需要做O(log2(n))随机节点读取找到一个值,B+树需要少量,例如O(log32(n)),因此每个节点分裂32路而不是2路。这在实践中有巨大的不同,到log2(2^32)≈32,log32(2^32)≈6.4查找。每个查找是随机访问,这对于具有旋转盘的硬盘来说是非常昂贵的。SSD有助于延迟,但是I/O的节省仍然存在。默认情况下,

ValueRef存储的值,期望字节为值(直接传递到存储)。二叉树节点本身只是ValueRef的子帧。通过json或msgpack存储更丰富的数据,这是将其设置为value_ref_class的问题。BinaryNodeRef是使用pickle串行化数据的一个例子。数据库压缩是另一个有趣的练习。压缩可以通过树的中值遍历遍历树。这可能是最好的树节点都在一起,因为他们是遍历找到的所有数据。将尽可能多的中间节点包装到磁盘扇区提高读取性能,至少在紧缩之后。这里有一些细微之处(例如,内存使用),如果你试图实现这一点。并记住:总是基准性能增强前后!你会发现惊讶的结果。

模式和原则

测试接口没有实现。作为开发DBDB的一部分,我写了一些测试,描述了我想要如何使用它。第一个测试针对内存版本的数据库运行,然后我将DBDB扩展到持久化磁盘,甚至后来添加了

NodeRefs的概念。大多数测试没有必要改变,这让我有信心继续做下去。尊重单一责任原则。类最多只能有一个理由改变。这不是DBDB的情况,但有多个扩展途径,只需要本地化更改。

总结

DBDB是一个简单的数据库,但程序仍然是复杂的。我管理这种复杂性的最重要的是实现一个具有不可变的数据结构的表面上可变的对象。我鼓励你考虑这种技术,下一次你发现自己在一个棘手的问题,似乎有更多的边缘情况,你可以继续跟踪。

引用

-

Bonus feature: Can you guarantee that the compacted tree structure is balanced? This helps maintain performance over time.↩

-

Calling fsync on a file descriptor asks the operating system and hard drive (or SSD) to write all buffered data immediately. Operating systems and drives don’t usually write everything immediately in order to improve performance.↩

-

-

500 Lines or Less Chapter 5: A Web Crawler With asyncio Coroutines 翻译

作者是来自纽约A. Jesse Jiryu Davis是的工程师A. Jesse Jiryu Davis。 他贡献asyncio和Tornado在http://reedysqua.re上。和Python之父Guido van Rossum。 Guido的博客地址是http://www.python.org/~guido/。

引言

经典计算机科学强调的是高效算法,尽可能快地完成计算。但许多网络程序更多的时间不是用在计算,而是缓慢的打开许多链接,或者处理一些不常见的情况。其中的挑战是:高效地等待大量的网络事件。当前处理这个问题的方法是异步I/O。

本章介绍一个简单的网络爬虫。爬虫也是一个异步应用程序,它等待很多响应但计算量很少。一次获取的页面越多,越早完成程序。如果它将线程分配给每个请求,则随着并发请求数量的增加,它将耗尽内存或其他线程的相关资源,直到它耗尽套接字。通过使用异步I/O避开对线程的需求。

我们在三个阶段提出的例子。首先,展示一个异步事件循环,并使用带回调的事件循环的爬虫:这非常有效,但是扩展到更复杂的问题将导致无法管理代码。第二,因此表明Python协程是高效和可扩展的。我们使用生成器函数在Python中实现简单的协同程序。在第三阶段,使用来自Python标准库里的

asyncio的协同程序,并使用异步队列来协调它们。任务

网络抓取工具查找和下载网站上的所有网页,也可以对其进行归档或编制索引。 从根URL开始,它获取每个页面,解析它的链接到没打开的的页面,并将它们添加到队列中。当它获取没打开的的页面的链接并且队列为空时,停止工作。

我们可以通过同时下载多页来加快这个过程。当爬虫找到新链接时,它会在单独的套接字上启动新页面的同步抓取操作。在响应到达时解析响应,向队列添加新链接。可能会出现一些减少返回的点,其中过多的并发性降低性能,因此我们限制并发请求的数量,并将剩余的链接留在队列中,直到请求完成。

传统的方法

我们如何实现爬行器并发? 传统的方法里,我们创建一个线程池。每个线程将负责通过套接字一页页下载。例如,要从

xkcd.com下载一个页面:def fetch(url): sock = socket.socket() sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url) sock.send(request.encode('ascii')) response = b'' chunk = sock.recv(4096) while chunk: response += chunk chunk = sock.recv(4096) # Page is now downloaded. links = parse_links(response) q.add(links)默认情况下,套接字操作是阻塞的:当线程调用leisi connect或recv的方法时,它会停止直到操作完成。因此,为了一次下载多个页面,我们需要许多线程。一个复杂的应用程序通过将线程池中的空闲线程保持在线程池中,然后将它们检出以重用它们用于后续任务来摊销线程创建的成本;它对连接池中的套接字执行相同操作。

但是线程成本昂贵的,而且操作系统对进程,操作系统对一个进程、一个用户、一台机器能使用线程做了不同的硬性限制。在Jesse的系统中,Python线程需要大约50k的内存,并且启动数以万计的线程就会导致失败。如果我们在并发套接字上扩展到数万个并发操作,我们就会耗尽线程用完套接字。每个线程的开销和系统的限制就是这种方式的瓶颈所在。

在他其有影响的文章”The C10K problem”中,Dan Kegel概述了I/O并发的多线程的局限性。

如今网络服务器要同时处理一万个客户端,你不这么觉得吗?毕竟,网络规模已经很大了。凯格尔在1999年创造了”C10K”这个术语。一万个连接现在听起来很好,但其实也只是在尺寸上变化。那时,使用C10K的每个连接的线程是不切实际的。现在是更高的数量级。事实上,我们的网络爬虫使用线程正常工作。然而对于非常大规模的应用程序,有成千上万的连接,仍然存在上限:超过该限制大多数系统仍然可以创建套接字,在耗尽了线程的时候。我们应该如何克服这一点?

异步

异步I/O框架使用非阻塞套接字在单个线程上执行并行操作。在我们的异步爬虫中,在我们连接到服务器之前设置套接字无阻塞:

sock = socket.socket() sock.setblocking(False) try: sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) except BlockingIOError: pass令人恼火的是非阻塞套接字抛出异常,即使它正常工作。这个异常复制了底层C函数讨人厌的行为,它将

errno设置为EINPROGRESS来告诉你它已经开始工作。现在我们的爬虫需要一种方法来确定连接何时建立,才可以发送HTTP请求。 我们可以写一个简单的循环:

request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url) encoded = request.encode('ascii') while True: try: sock.send(encoded) break # Done. except OSError as e: pass print('sent')这种方法不仅耗CPU,而且不能有效地等待多个套接字。 过去BSD Unix的解决这个问题的解决方案是选择一个C函数,等待一个事件发生在一个非阻塞的套接字或一个小数组。 如今,对具有大量连接的互联网应用的需求导致了诸如’poll’的替换,然后是BSD的

kqueue和Linux上的epoll。这些类似于select的API,但是对于非常大量的连接非常有效。Python 3.4的

DefaultSelector使用系统上可用的最佳选择函数。要注册有关网络I/O 的提醒,我们需要创建一个非阻塞套接字并使用默认选择器注册它:from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_WRITE selector = DefaultSelector() sock = socket.socket() sock.setblocking(False) try: sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) except BlockingIOError: pass def connected(): selector.unregister(sock.fileno()) print('connected!') selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_WRITE, connected)我们忽略了这个伪错误并调用

selector.register,传递套接字的文件描述符和一个常量,代表我们正在等待的事件。 要在连接建立时通知,我们传递EVENT_WRITE:也就是说,我们想知道套接字何时是”可写的”。 我们还传递一个Python函数,connected当事件发生时运行。该函数称为回调。当选择器接收到它们时,我们在一个循环中处理I/O通知:

def loop(): while True: events = selector.select() for event_key, event_mask in events: callback = event_key.data callback()这个

connected回调被存储为event_key.data,一旦非阻塞套接字被连接便检索和执行。不像前面的快速循环,这里

select暂停调用,等待下一个I/O事件。然后循环运行等待这些事件的回调。尚未完成的操作将保持pending,直到进到下一个事件循环时执行。到目前为止我们展示了什么?我们展示了如何开始I/O操作和执行回调。异步框架建立展示的两个特性(非阻塞套接字和事件循环),以在单个线程上运行并发操作。

我们在这里实现了“并发”,但不是传统上被称为“并行性”。也就是说,我们构建了一个重叠I/O的小系统。它能够开始新的行动,而其他也在操作。它实际上并不利用多个核来并行执行计算。但是,这个系统是为I/O绑定的问题设计的,而不是CPU限制的。

因此,我们的事件循环在并发I/O方面是高效的,因为它不会将线程资源分配给每个连接。但在我们继续前,纠正一个常见的误解,即异步的速度比多线程快。通常不是,事实上在Python中,像我们这样的事件循环比服务少数非常活跃的连接的多线程慢。在没有全局解释器锁的运行时,线程在这样的工作负载上表现更好。“什么是异步,它如何工作,什么时候该用它?”一文中指出了异步所适用和不适用的场景。

回调

目前我们已经构建异步框架,将如何继续构建一个网络爬虫? 即使写一个简单的URL爬取也是痛苦的是痛苦。

我们先从全局的URL集合开始,我们看到的URL:

urls_todo = set(['/']) seen_urls = set(['/'])seen_urls集里包括urls_todo加完成的URL。这两个集合用于初始化URL“/”。获取页面将需要一系列回调。

connected在连接套接字时触发回调,并向服务器发送GET请求。但是它必须等待响应,所以需要注册另一个回调。 如果,当回调触发时,它不能读取完整的响应,它再次注册,等等。让我们把这些回调放在一个

Fetcher对象中,它需要一个URL,一个套接字,还需要一个地方保存返回的字节:class Fetcher: def __init__(self, url): self.response = b'' # Empty array of bytes. self.url = url self.sock = None我们开始调用

Fetcher.fetch# Method on Fetcher class. def fetch(self): self.sock = socket.socket() self.sock.setblocking(False) try: self.sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) except BlockingIOError: pass # Register next callback. selector.register(self.sock.fileno(), EVENT_WRITE, self.connected)fetch函数开始连接套接字。 但请注意,该方法在建立连接之前返回。 它必须将控制权返回到事件循环,以等待连接。为了理解为什么,想象我们的整个应用程序的结构:# Begin fetching http://xkcd.com/353/ fetcher = Fetcher('/353/') fetcher.fetch() while True: events = selector.select() for event_key, event_mask in events: callback = event_key.data callback(event_key, event_mask)所有事件提醒在调用

select时在事件循环中处理。 因此,fetch必须手动控制到事件循环,以便程序知道套接字何时连接。 只有这样,循环才会运行连接的回调,这在fetch的结尾处注册。以下是实现

connected的代码:# Method on Fetcher class. def connected(self, key, mask): print('connected!') selector.unregister(key.fd) request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(self.url) self.sock.send(request.encode('ascii')) # Register the next callback. selector.register(key.fd, EVENT_READ, self.read_response)该方法发送

GET请求。真正的应用程序将检查send的返回值,以防整个消息不能立即发送。不过这里的程序不复杂。 它调用send,然后等待响应。当然,它必须注册另一个回调,并放弃对事件循环的控制。 最后一个回调read_response处理服务器的回应:# Method on Fetcher class. def read_response(self, key, mask): global stopped chunk = self.sock.recv(4096) # 4k chunk size. if chunk: self.response += chunk else: selector.unregister(key.fd) # Done reading. links = self.parse_links() # Python set-logic: for link in links.difference(seen_urls): urls_todo.add(link) Fetcher(link).fetch() # <- New Fetcher. seen_urls.update(links) urls_todo.remove(self.url) if not urls_todo: stopped = True每次选择器看到套接字是“可读的”时,就会执行回调,这意味着:套接字有数据或已关闭。

回调从套接字请求最多4千字节的数据。如果更少,

chunk包含任何可用的数据。如果有更多,chunk有4千字节长,并且套接字保持可读,因此事件循环在下一个响应时再次运行这个回调。当响应完成时,服务器已关闭套接字并且chunk为空。parse_links方法返回一组URL。我们为每个新网址开始一个新的抓取器,没有并发上限。注意使用回调的异步编程的一个很好的功能:我们不需要围绕共享数据的变化的互斥,例如当我们添加链接到seen_urls。 没有优先的多任务,所以我们不能在代码中的任意点被打断。我们添加一个全局

stop变量,并使用它来控制循环:stopped = False def loop(): while not stopped: events = selector.select() for event_key, event_mask in events: callback = event_key.data callback()一旦下载所有页面,抓取器会停止全局事件循环,程序退出。

这个例子使异步问题变得很简单。我们需要一些方法来表达一系列计算和I/O操作,并且调度多个一系列操作以并发运行。但是没有线程,一系列操作不能被收集到单个函数中:每当一个函数开始I/O操作时,它显式地保存将来所需要的任何状态,然后返回。 你可以思考以下如何编写这个状态节省代码。

让我们来解释一下。考虑我们如何简单地在一个具有常规阻塞套接字的线程上获取一个URL:

# Blocking version. def fetch(url): sock = socket.socket() sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) request = 'GET {} HTTP/1.0\r\nHost: xkcd.com\r\n\r\n'.format(url) sock.send(request.encode('ascii')) response = b'' chunk = sock.recv(4096) while chunk: response += chunk chunk = sock.recv(4096) # Page is now downloaded. links = parse_links(response) q.add(links)这个函数在一个套接字操作和下一个套接字操作之间记录了什么?它有套接字,一个URL和积累的

response。在线程上运行的函数使用编程语言的基本特性将该临时状态存储在其堆栈中的局部变量中。该函数还有一个“继续”,即它计划在I/O完成后执行的代码。运行时通过存储线程的指令指针来记住。您不必考虑恢复这些局部变量和I/O后的继续。它是内置的语言。但是使用基于回调的异步框架,这些语言功能并没有什么帮助。在等待I/O时,函数必须显式地保存其状态,因为该函数在I/O完成之前返回并丢失其堆栈。Fetcher实例中我们的基于回调存储的

sock和response作为self的属性。代替指令指针,它通过注册connected的回调和read_response来存储它的连续。随着应用程序的功能增加,我们在回调中手动保存状态的复杂性也在增加。更糟的是,如果回调引发异常,在调度链中的下一个回调之前会发生什么?所以在

parse_links方法上做的并不好,它抛出解析HTML的异常:Traceback (most recent call last): File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 111, in <module> loop() File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 106, in loop callback(event_key, event_mask) File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 51, in read_response links = self.parse_links() File "loop-with-callbacks.py", line 67, in parse_links raise Exception('parse error') Exception: parse error堆跟踪仅显示事件循环正在运行回调。我们不记得是什么导致的错误。链条在两端都断了:我们忘了我们去哪里,我们为何而来。这种上下文的丢失被称为“stack ripping”,并且在许多情况下它混淆了研究者。堆栈翻录还阻止我们为回调链安装异常处理程序,“try/except”块包装函数调用及其后代的方式.

因此,除了关于多线程和异步的相对效率的长期争论之外,还有另一个争论是更容易出错的:如果你使错误同步它们,线程就容易受到数据竞争,但是回调是固执的调试由于堆栈翻录。

协同

可以编写异步代码,将回调的效率与多线程编程的经典好看结合起来。这种组合是通过“协同程序”的模式来实现。使用Python3.4的标准asyncio库和“aiohttp”的包,在协程中非常直接获取URL:

@asyncio.coroutine def fetch(self, url): response = yield from self.session.get(url) body = yield from response.read()它也是可扩展的。与每个线程的50k内存和操作系统对线程的硬限制相比,Python协程在Jesse的系统上只需要3k的内存。 Python可以轻松启动数十万个协程。

协同程序的概念,可以追溯到很早以前的计算机科学:它是一个可以暂停和恢复的子程序。而线程是由操作系统抢占式多任务,协同多任务协作:他们选择何时暂停,以及哪个协程运行下一步。

有很多协同程序的实现,在Python就有好几个。Python3.4中的标准“asyncio”库中的协程是基于生成器,Future类和“yield from”语句构建的。从Python3.5开始,协程是语言本身的一个本地特性;然而,了解协同程序,,使用预先存在的语言设施,是解决Python3.5的本地协同程序的基础。

为了解释Python3.4的基于生成器的协同程序,我们将介绍一些生成器以及它们如何在asyncio中用作协程,并且相信你会喜欢阅读它。一旦我们解释了基于生成器的协同程序,我们将使用它们在我们的异步Web爬虫。

Python生成器如何工作

在掌握Python生成器之前,您必须了解常规Python函数的工作原理。通常,当Python函数调用子例程时,子例程保留控制,直到返回或抛出异常。然后控制权返回给调用者:

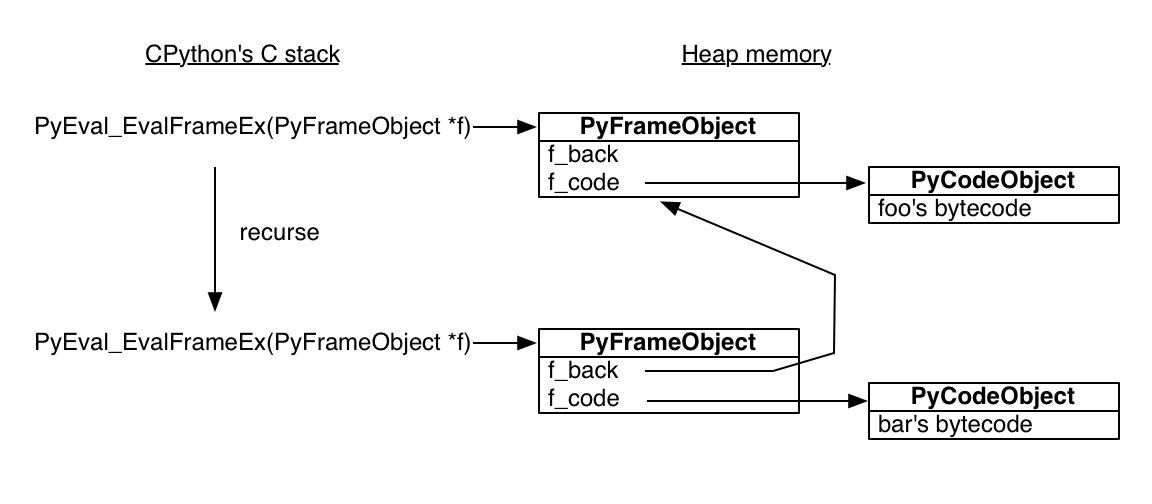

>>> def foo(): ... bar() ... >>> def bar(): ... pass标准的Python解释器是用C编写的。执行Python函数的C函数被称

PyEval_EvalFrameEx。它需要一个Python栈框架对象,并在框架的上下文中评估Python字节码。 这里是foo的字节码:>>> import dis >>> dis.dis(foo) 2 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (bar) 3 CALL_FUNCTION 0 (0 positional, 0 keyword pair) 6 POP_TOP 7 LOAD_CONST 0 (None) 10 RETURN_VALUEfoo函数加载bar到其堆中调用,然后从堆中弹出其返回值,将None加载到堆栈,并返回None。当

PyEval_EvalFrameEx遇到CALL_FUNCTION字节码时,它会递归创建一个新的Python栈:也就是说,它使用新的堆递归调用PyEval_EvalFrameEx,用于执行bar。了解Python堆栈帧在堆内存中分配是很重要的!Python解释器是一个C程序,所以它的堆框架也是正常的堆栈帧。但Python堆框架是在建立堆上。 除此之外,这意味着Python堆框架可以为其函数调用。要以交互方式查看,从

bar保存当前的框架>>> import inspect >>> frame = None >>> def foo(): ... bar() ... >>> def bar(): ... global frame ... frame = inspect.currentframe() ... >>> foo() >>> # The frame was executing the code for 'bar'. >>> frame.f_code.co_name 'bar' >>> # Its back pointer refers to the frame for 'foo'. >>> caller_frame = frame.f_back >>> caller_frame.f_code.co_name 'foo'

该阶段是设置Python生成器,使用相同的构建块 - 代码对象和堆。

这是一个生成器函数:

>>> def gen_fn(): ... result = yield 1 ... print('result of yield: {}'.format(result)) ... result2 = yield 2 ... print('result of 2nd yield: {}'.format(result2)) ... return 'done' ...当Python将

gen_fn编译为字节码时,它会看到yield状态,并且知道gen_fn是一个生成器函数,而不是一个常规函数。 它设置一个标志记住:>>> # The generator flag is bit position 5. >>> generator_bit = 1 << 5 >>> bool(gen_fn.__code__.co_flags & generator_bit) True当你调用一个生成器函数,Python看到生成器标志,它实际上并不运行该函数。 相反,它创建一个生成器:

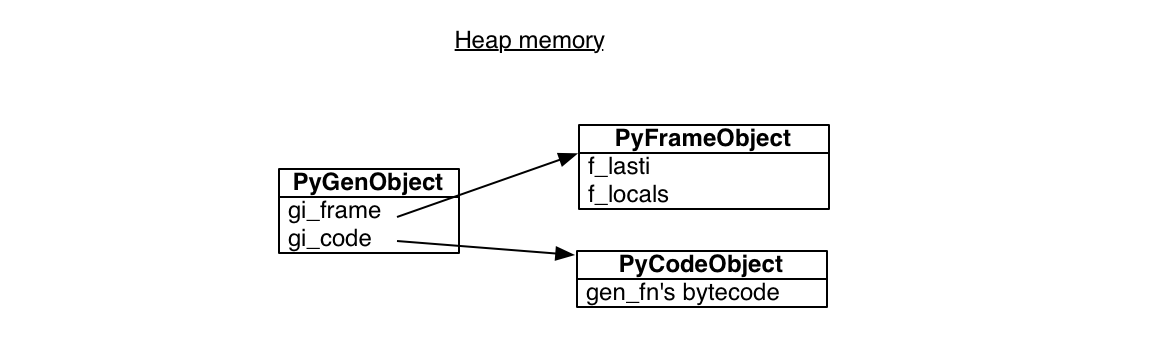

>>> gen = gen_fn() >>> type(gen) <class 'generator'>Python生成器封装了一个堆和一些代码的引用,

gen_fn的主体:>>> gen.gi_code.co_name 'gen_fn'所有从

gen_fn调用的生成器都指向这个相同的代码。但每个都有自己的堆。 这个堆栈帧不在任何实际堆中,它坐在栈内存等待使用:

该框架具有“last instruction”指针,它是最新执行的指令。 开始时,last instruction指针是-1,表示生成器尚未开始:

>>> gen.gi_frame.f_lasti -1当我们调用

send时,生成器到底第一个yield并且暂停。send的返回值是1,因为这是gen传递给yield表达式:>>> gen.send(None) 1生成器的指令指针现在是从开始的3个字节码,部分通过编译的Python的56个字节:

>>> gen.gi_frame.f_lasti 3 >>> len(gen.gi_code.co_code) 56生成器可以在任何时候从任何函数恢复,因为它的堆实际上不在堆上:它在栈上。它在调用层次结构中的位置 不固定的,并且它不需要遵守常规函数执行的先进先出顺序。

我们可以将值“hello”发送到生成器,它成为

yield表达式的结果,并且生成器继续,直到它产生yield 2:>>> gen.send('hello') result of yield: hello 2它的堆现在包括了局部变量

result>>> gen.gi_frame.f_locals {'result': 'hello'}从

gen_fn创建的其他生成器将有自己的堆和局部变量。当我们再次调用

send时,生成器继续通过它的第二个yield,并抛出特别的StopIteration异常结束:>>> gen.send('goodbye') result of 2nd yield: goodbye Traceback (most recent call last): File "<input>", line 1, in <module> StopIteration: done这个异常有一个值,它是生成器的返回值:字符串“done”。

使用生成器构建协同程序

从保存的值恢复,具有返回值。听起来很好地构建一个异步编程模型。 我们想建立一个“协同程序”:一个与程序中的其他程序一起调度的程序。 我们的协程将是Python标准“asyncio”库中的简化版本。 在asyncio中,我们将使用generator,futures和“yield from”语句。

首先,我们需要一种方法来表示协同程序正在等待的未来结果。精简的版本如下:

class Future: def __init__(self): self.result = None self._callbacks = [] def add_done_callback(self, fn): self._callbacks.append(fn) def set_result(self, result): self.result = result for fn in self._callbacks: fn(self)future 初始时pending,它通过调用

set_result解析。让我们使用futures和coroutines来调整抓取器。通过回调来写

fetchclass Fetcher: def fetch(self): self.sock = socket.socket() self.sock.setblocking(False) try: self.sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) except BlockingIOError: pass selector.register(self.sock.fileno(), EVENT_WRITE, self.connected) def connected(self, key, mask): print('connected!') # And so on....fetch方法开始连接套接字,然后注册回调,connected,当套接字准备好时执行。现在我们可以将这两个步骤组合成一个协同程序def fetch(self): sock = socket.socket() sock.setblocking(False) try: sock.connect(('xkcd.com', 80)) except BlockingIOError: pass f = Future() def on_connected(): f.set_result(None) selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_WRITE, on_connected) yield f selector.unregister(sock.fileno()) print('connected!')现在

fetch是一个生成器函数,而不是一个常规函数,因为它包含yield语句。我们创建一个pending future,然后让它暂停fetch直到套接字准备就绪。内部函数on_connected解析future。但是,当future解析式,是什么重启生成器呢? 我们需要一个协程驱动程序。 称之为“任务”:

lass Task: def __init__(self, coro): self.coro = coro f = Future() f.set_result(None) self.step(f) def step(self, future): try: next_future = self.coro.send(future.result) except StopIteration: return next_future.add_done_callback(self.step) # Begin fetching http://xkcd.com/353/ fetcher = Fetcher('/353/') Task(fetcher.fetch()) loop()任务通过向其发送

None来启动fetch生成器。 然后fetch运行,直到它产生一个future,任务用next_future捕获。当套接字连接时,事件循环运行回调on_connected,它解析future调用step,恢复fetch。用

yield from转换协同一旦套接字连接,我们发送HTTP GET请求并读取服务器响应。 这些步骤不再分散在回调中; 我们将它们收集到相同的生成函数中:

def fetch(self): # ... connection logic from above, then: sock.send(request.encode('ascii')) while True: f = Future() def on_readable(): f.set_result(sock.recv(4096)) selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_READ, on_readable) chunk = yield f selector.unregister(sock.fileno()) if chunk: self.response += chunk else: # Done reading. break这个代码从套接字读取整个消息。我们如何将它从

fetch转换为子程序? 现在Python3的yield from接管了这个阶段。 它把一个生成器委托给另一个。让我们回到我们简单的生成器示例:

>>> def gen_fn(): ... result = yield 1 ... print('result of yield: {}'.format(result)) ... result2 = yield 2 ... print('result of 2nd yield: {}'.format(result2)) ... return 'done' ...要从另一个生成器调用此生成器,请使用

yield:>>> # Generator function: >>> def caller_fn(): ... gen = gen_fn() ... rv = yield from gen ... print('return value of yield-from: {}' ... .format(rv)) ... >>> # Make a generator from the >>> # generator function. >>> caller = caller_fn()caller生成器就像是gen,它被委托给:>>> caller.send(None) 1 >>> caller.gi_frame.f_lasti 15 >>> caller.send('hello') result of yield: hello 2 >>> caller.gi_frame.f_lasti # Hasn't advanced. 15 >>> caller.send('goodbye') result of 2nd yield: goodbye return value of yield-from: done Traceback (most recent call last): File "<input>", line 1, in <module> StopIteration当

calleryield fromgen1,caller不继续往前。它的指令指针保持在15,它的yield from的位置,即使内部生成器gen从一个yield语句到下一个。从caller外部,我们无法知道它产生的值是从caller或从其委派的生成器。从gen内部,我们不能知道值是从caller还是从外部发送。yield from是一个无摩擦通道,从它的值输入和gen输出直到gen完成。协同程序可以将工作委托给一个有

yield from子协同程序,并从中接收工作结果。 注意,上面caller打印“return value of yield-from: done”。 当gen完成时,其返回值成为caller中yield from的值:rv = yield from gen早些时候,当我们批评基于回调的异步编程时,我们最强烈的投诉是”“stack ripping”:当回调抛出异常时,堆跟踪通常是无用的。它只显示事件循环正在运行回调,而不是为什么。协程如何运行?

>>> def gen_fn(): ... raise Exception('my error') >>> caller = caller_fn() >>> caller.send(None) Traceback (most recent call last): File "<input>", line 1, in <module> File "<input>", line 3, in caller_fn File "<input>", line 2, in gen_fn Exception: my error这更有用! 堆跟踪显示

caller_fn在委托gen_fn时抛出错误。 更令人欣慰的是,我们可以将调用包装到异常处理程序中的子协程,同样使用正常的子程序:>>> def gen_fn(): ... yield 1 ... raise Exception('uh oh') ... >>> def caller_fn(): ... try: ... yield from gen_fn() ... except Exception as exc: ... print('caught {}'.format(exc)) ... >>> caller = caller_fn() >>> caller.send(None) 1 >>> caller.send('hello') caught uh oh因此,我们用子协同因子转换逻辑,就像使用常规子程序一样。 让我们用抓取器转化一些有用的子协程。我们写一个

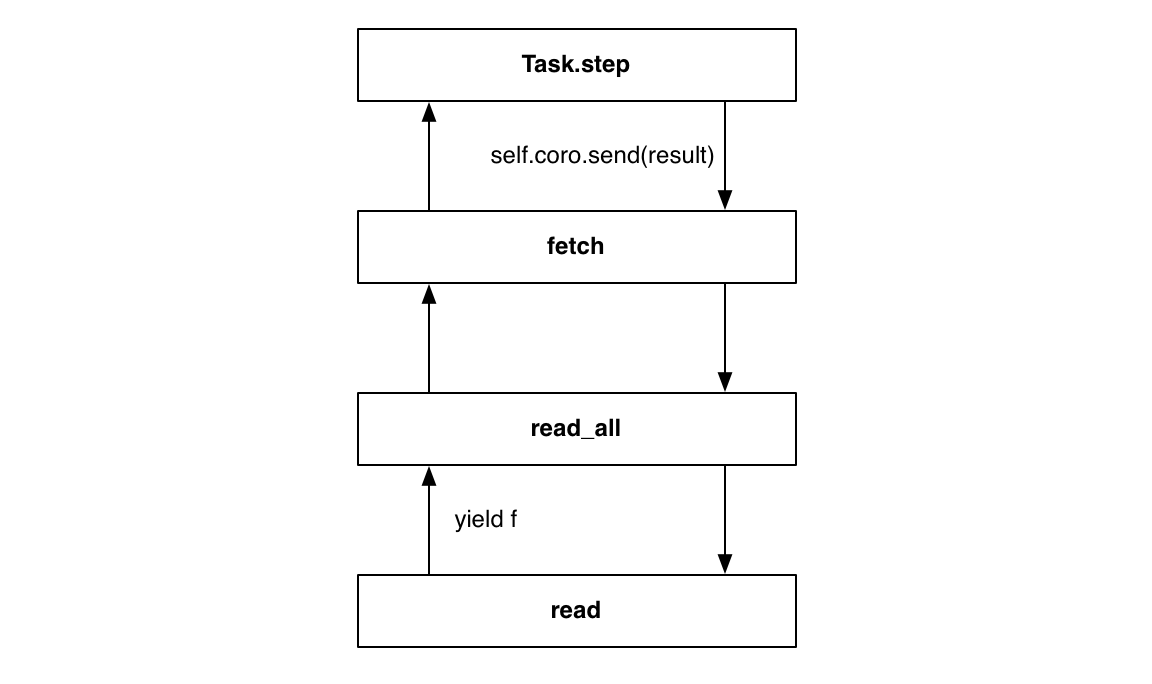

read协程来接收块:def read(sock): f = Future() def on_readable(): f.set_result(sock.recv(4096)) selector.register(sock.fileno(), EVENT_READ, on_readable) chunk = yield f # Read one chunk. selector.unregister(sock.fileno()) return chunk用

read_all协程来构建read,获取所有的信息def read_all(sock): response = [] # Read whole response. chunk = yield from read(sock) while chunk: response.append(chunk) chunk = yield from read(sock) return b''.join(response)如果你以正确的方式倾斜,

yield from消失,这看起来像阻塞I/O的常规函数。但事实上,read和read_all是协程。read暂停read_all直到I/O完成。当read_all暂停时,异步事件循环执行其他工作,并等待其他I/O事件;read_all在恢复事件准备好后,在下一个循环上读取的结果。在堆根目录,

fetch调用read_all:class Fetcher: def fetch(self): # ... connection logic from above, then: sock.send(request.encode('ascii')) self.response = yield from read_all(sock)奇怪的是,Task类不需要修改。它和之前一样驱动外部

fetch协同程序:Task(fetcher.fetch()) loop()当

read产生future时,任务通过yield from语句的通道获取,就好像future直接从fetch产生。 当循环解析future时,任务将其结果发送到fetch,并且read接收该值,就好像任务直接驱动read一样:

为了完善协程,我们抛出一个错误:在等待未来时使用

yield,当它委托给一个子协程时yield from。我们利用Python生成器和迭代器之间的深层对应。 推进生成器对于调用者,与推进迭代器相同。 所以我们通过一个特殊的方法使我们的Future类可迭代:

# Method on Future class. def __iter__(self): # Tell Task to resume me here. yield self return self.resultfuture的

__iter__方法是yield future的协程。现在我们使用以下的代码:# f is a Future. yield f用这个:

# f is a Future. yield from f结果是一样的!驱动Task从其调用

send获取future,当未来被解析时,其将新的结果发送回协同。使用

yield from有什么优点?为什么用yield等待future和用yield from委托到子协同更好?因为它可以自由地改变其实现而不影响调用者:它可能是一个正常的方法返回future将解析为一个值,它也可能是包含yield from语句的协同程序,并返回值。在任何一种情况下,调用者只需要从方法中yield,以便等待结果。我们已经完成异步协作。我们探讨了生成器的机制,并且实现了future和task,概述了如何更好地实现两个世界的异步:并发I/O比线程更有效,比回调更清晰。当然,真正异步比这个更加复杂。真正的框架解决了零拷贝I/O,公平调度,异常处理和许多其他功能。

对于asyncio用户,用协同程序编码比你在这里看到的要简单得多。在上面的代码中,我们第一个原则实现协程,所以你看到回调,任务和future。你甚至看到非阻塞套接字和调用

select。但是当使用asyncio构建应用程序时,这些都不会出现在您的代码中。你现在已经可以顺利地获取一个URL:@asyncio.coroutine def fetch(self, url): response = yield from self.session.get(url) body = yield from response.read()我们回到我们原来的任务:写一个异步的网络爬虫,使用asyncio。

协调协同

我们开始描述我们希望抓取器如何工作。现在来实现它与asyncio协程。

我们的抓取器会抓取第一页,解析其链接,并将其添加到队列中。在这之后,它打开网站,同时抓取页面。但是为了限制客户端和服务器上的负载,我们希望运行一些最大数量的工作。每当完成提取页面时,它应该立即从队列中拉下一个链接。我们将过去没有足够的工作周期,所以一些工作必须暂停。但是当一个工作者点击一个新链接的页面时,队列突然编程,任何暂停的工作者都应该醒来并开始破解。最后,我们的程序必须在其工作完成后退出。

想象一下,如果工作是线程。我们将如何表达爬虫的算法?我们可以使用Python标准库中的同步队列。每次将项目放入队列时,队列都会增加其“任务”的计数。完成项目工作后,工作线程调用

task_done。主线程在Queue.join上阻塞,直到每个放入队列的项目被一个task_done调用匹配,然后它退出。协程使用与asyncio队列完全相同的模式!首先我们导入::

try: from asyncio import JoinableQueue as Queue except ImportError: # In Python 3.5, asyncio.JoinableQueue is # merged into Queue. from asyncio import Queue我们在爬虫类中收集工作的共享状态,并在

crawl方法中写入主逻辑。 我们在协程上开始crawl,并运行asyncio的事件循环,直到crawl完成:loop = asyncio.get_event_loop() crawler = crawling.Crawler('http://xkcd.com', max_redirect=10) loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())抓取器以根网址和

max_redirect开头。它把一对(URL,max_redirect)放入队列。class Crawler: def __init__(self, root_url, max_redirect): self.max_tasks = 10 self.max_redirect = max_redirect self.q = Queue() self.seen_urls = set() # aiohttp's ClientSession does connection pooling and # HTTP keep-alives for us. self.session = aiohttp.ClientSession(loop=loop) # Put (URL, max_redirect) in the queue. self.q.put((root_url, self.max_redirect))队列中未完成任务的数量现在为1。回到我们的主要脚本,我们启动事件循环和

crawl方法:loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())crawl协程启动工作。它就像一个主线程:它阻塞在join直到所有任务完成,而工作在后台运行。@asyncio.coroutine def crawl(self): """Run the crawler until all work is done.""" workers = [asyncio.Task(self.work()) for _ in range(self.max_tasks)] # When all work is done, exit. yield from self.q.join() for w in workers: w.cancel()如果工作是线程,我们可能不希望立即启动它们。为了避免在确定需要之前创建昂贵的线程,线程池通常根据需要增长。 但协同程序很容易,所以我们只是启动允许的最大数量。

有趣的是注意我们如何关闭抓取器。 当加入

joinfuture解析时,工作任务仍然存活,但被暂停:它们等待更多的URL。因此,主协同程序在退出之前取消它们。否则,当Python解释器关闭并调用所有对象的析构函数时:ERROR:asyncio:Task was destroyed but it is pending!cancel如何工作的? 生成器具有我们尚未向您展示的功能。 您可以从外部将异常抛出到生成器中:>>> gen = gen_fn() >>> gen.send(None) # Start the generator as usual. 1 >>> gen.throw(Exception('error')) Traceback (most recent call last): File "<input>", line 3, in <module> File "<input>", line 2, in gen_fn Exception: error生成器通过

throw恢复,但它现在引发异常。如果生成器的调用栈中没有代码捕获它,则异常回到顶部。所以要取消任务的协程:# Method of Task class. def cancel(self): self.coro.throw(CancelledError)无论生成器何时暂停,在某些

yield语句,它将恢复并引发异常。我们在step方法中处理取消:# Method of Task class. def step(self, future): try: next_future = self.coro.send(future.result) except CancelledError: self.cancelled = True return except StopIteration: return next_future.add_done_callback(self.step)现在任务知道它被取消。

一旦

crawl已取消工人,它退出。 事件循环看到协同程序是完整的(我们将看到稍后),它也退出:loop.run_until_complete(crawler.crawl())crawl方法包含了我们的主协同程序必须做的所有函数。它是协程工作,从队列获取URL,并解析它们的新链接。 每个work独立地运行工作协同:@asyncio.coroutine def work(self): while True: url, max_redirect = yield from self.q.get() # Download page and add new links to self.q. yield from self.fetch(url, max_redirect) self.q.task_done()Python看到这个包含

yield from语句的代码,并将其编译成一个生成函数。 因此在抓取时,当主协同程序调用self.work十次时,它实际上不执行此方法:只啊创建十个生成器对象引用此代码。 它将每个任务包装在一个任务中。任务接收每个future的生成器yield,并且通过在future解析时通过调用具有每个future解析结果的sending。 因为生成器具有自己的堆,所以它们独立运行,具有单独的局部变量和指令指针。工作通过队列与其他工作协调。它等待具有以下内容的URL:

url, max_redirect = yield from self.q.get()队列里的

get方法本身是一个协程:它暂停直到有项目被放入队列中,然后恢复并返回。顺便说一下,工作将在抓取结束时暂停,当主协同程序取消它。 从协同程序的角度来看,最后一个行程循环结束,当

yield from抛出CancelledError。当工作提取页面时,它将解析链接并将新的链接放入队列,然后调用·task_done·以递减计数器。最终,工作获取已经获取了URL的页面,并且队列中也没有剩余的工作。 因此,对

task_done的调用将计数器减少为零。等待队列的join方法的crawl被取消暂停并结束。我们来解释下为什么队列中的项目是成对的,如:

# URL to fetch, and the number of redirects left. ('http://xkcd.com/353', 10)新URL有十个重定向。获取此特定网址会导致重定向到带有尾部斜杠的新位置。 我们减少剩余的重定向数,并将下一个位置放入队列:

# URL with a trailing slash. Nine redirects left. ('http://xkcd.com/353/', 9)我们使用的

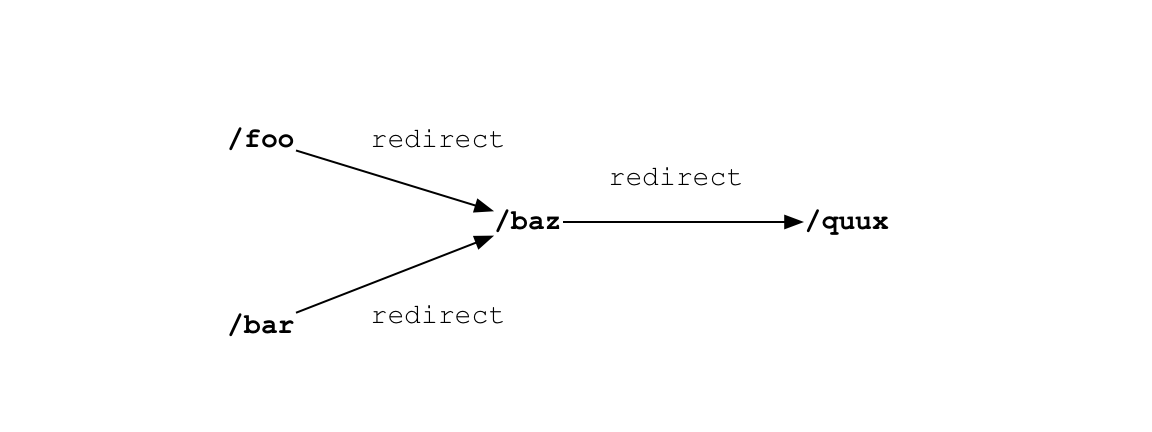

aiohttp包将遵循重定向默认情况下,并给我们最后的答复。然而,我们告诉它不会在抓取工具中处理重定向,因此它可以合并导致同一目的地的重定向路径:如果我们已经看到这个URL,它在self.seen_urls,我们已经开始在这个路径的不同入口点:

抓取器提取“foo”并看到它重定向到“baz”,所以它将“baz”添加到队列和

seen_urls中。 如果它获取的下一页是“bar”,它也会重定向到“baz”,抓取器不会再次入队“baz”。如果响应是一个页面,而不是重定向,fetch解析它的链接,并将新的队列中。@asyncio.coroutine def fetch(self, url, max_redirect): # Handle redirects ourselves. response = yield from self.session.get( url, allow_redirects=False) try: if is_redirect(response): if max_redirect > 0: next_url = response.headers['location'] if next_url in self.seen_urls: # We have been down this path before. return # Remember we have seen this URL. self.seen_urls.add(next_url) # Follow the redirect. One less redirect remains. self.q.put_nowait((next_url, max_redirect - 1)) else: links = yield from self.parse_links(response) # Python set-logic: for link in links.difference(self.seen_urls): self.q.put_nowait((link, self.max_redirect)) self.seen_urls.update(links) finally: # Return connection to pool. yield from response.release()如果这是多线程代码,那么它的竞争条件并不好。例如,工作程序检查链接是否在

seen_urls中,如果不是,则将其放入队列并将其添加到seen_urls中。如果它在两个操作之间中断,则另一个工作可以从不同的页面解析相同的链接,观察它不在seen_urls中,并且也将其添加到队列。现在同一个链接在队列中两次,导致重复的工作和错误的统计。然而,协程易受到

yield from的中断的影响。这是一个关键区别,使得协同代码比多线程代码更不容易发生竞争:多线程代码必须通过抓取锁显式地进入临界区,否则它是可中断的。Python协程在默认情况下是不可中断的,并且只有在它显式产生时才控制。我们不再需要像在基于回调的程序中一样的fetcher类。该类是回调不足的解决方法:在等待I/O时,它们需要一些地方来存储状态,因为它们的局部变量不会跨调用保留。但是

fetch协程可以像局部变量那样将其状态存储在局部变量中,则不再需要类。当

fetch完成处理服务器响应时,它返回到调用者work。工作方法在队列上调用task_done,然后从队列中获取要提取的下一个URL。当

fetch将新链接放入队列时,它会增加未完成任务的计数,并保持主协程,等待q.join,并且停止。但是,如果没有未看见的链接,并且这是队列中的最后一个URL,那么当工作调用task_done时,未完成任务的计数降为零。该事件取消暂停连接,主协同程序完成。协调工作和主协同程序的队列代码如下:

class Queue: def __init__(self): self._join_future = Future() self._unfinished_tasks = 0 # ... other initialization ... def put_nowait(self, item): self._unfinished_tasks += 1 # ... store the item ... def task_done(self): self._unfinished_tasks -= 1 if self._unfinished_tasks == 0: self._join_future.set_result(None) @asyncio.coroutine def join(self): if self._unfinished_tasks > 0: yield from self._join_future主协同程序

crawlyields fromjoin。因此,当最后一个工人将未完成任务的计数减少为零时,它表示crawl恢复且完成。进程基本结束。我们的程序从调用

crawl开始:loop.run_until_complete(self.crawler.crawl())程序将如何结束? 由于

crawl是一个生成器函数,因此调用它会返回一个生成器。为了驱动生成器,asyncio将它包装在任务中:class EventLoop: def run_until_complete(self, coro): """Run until the coroutine is done.""" task = Task(coro) task.add_done_callback(stop_callback) try: self.run_forever() except StopError: pass class StopError(BaseException): """Raised to stop the event loop.""" def stop_callback(future): raise StopError当任务完成时,它抛出

StopError,循环使用它作为已经到达正常完成的信号。但这是什么呢? 任务有

add_done_callback和result的方法?你可能认为任务类似于future。你的直觉是对的。我们隐藏了任务类的细节:任务是future。class Task(Future): """A coroutine wrapped in a Future."""通常,future通过调用

set_result解析。但是一个任务在它的协程停止时自主解析。我们之前探索Python生成器时说明了,当一个生成器返回时,它会抛出特殊的StopIteration异常:# Method of class Task. def step(self, future): try: next_future = self.coro.send(future.result) except CancelledError: self.cancelled = True return except StopIteration as exc: # Task resolves itself with coro's return # value. self.set_result(exc.value) return next_future.add_done_callback(self.step)所以当时间循环调用

task.add_done_callback(stop_callback)时,它可被任务停止。下面是run_until_complete代码:# Method of event loop. def run_until_complete(self, coro): task = Task(coro) task.add_done_callback(stop_callback) try: self.run_forever() except StopError: pass当任务捕获

StopIteration并解析自身时,回调会在循环中抛出StopError。循环停止,调用堆解开到run_until_complete。我们的程序这就完成了。结论

现代程序越来越多是I/O绑定而不是CPU绑定。对于这样的程序,Python线程是最糟糕的:全局解释器锁防止它们并行执行计算,并且优先切换使它们容易出现竞争。异步往往是正确的模式。但是随着基于回调的异步代码的增长,它往往成为一个混乱的混乱。协程是个替代品。则自然地考虑子程序,具有正确的异常处理和堆跟踪。

如果我们眯着眼睛,把

yield from变得模糊,协同程序看起来j就像一个线程做传统的阻塞I/O。我们甚至可以使用多线程编程中的经典模式来协调协同程序,没有必要改造。因此,与回调相比,协同程序是多线程所用的编码器是诱人的。但是当我们打开眼睛,专注于

yield from,我们看到他们标记点,当协程让出控制权,并允许其他运行。与线程不同,协同程序显示我们的代码可以中断而它不能。在他文章 “Unyielding”中,Glyph Lefkowitz写道:“线程使得局部推理变得困难,并且局部推理可能是软件开发中最重要的。然而,显式产生可以通过检查例程本身而不是检查整个系统来“理解例程的行为”。基于生成器的协同程序,它的设计你已学会了,在2014年3月的Python 3.4的“asyncio”模块中发布。2015年9月,Python 3.5发布了内置语言本身的协同程序。这些本地协程用新语法“async def”声明,而不是“yield from”,它们使用新的“await”关键字来委派协程或等待future。

Python的新本地协同程序将在语法上与生成器截然不同,但工作原理相似;实际上,他们将在Python解释器中统一实现。任务,future和事件循环将继续在asyncio中发挥他们的作用。

现在你知道asyncio协程如何工作,你可以忘记细节。但是你对基础知识的掌握使你能够在现代异步环境中正确有效地编码。

引用

-

Guido introduced the standard asyncio library, called “Tulip” then, at PyCon 2013.

-

Even calls to send can block, if the recipient is slow to acknowledge outstanding messages and the system’s buffer of outgoing data is full.

-

http://www.kegel.com/c10k.html

-

Python’s global interpreter lock prohibits running Python code in parallel in one process anyway. Parallelizing CPU-bound algorithms in Python requires multiple processes, or writing the parallel portions of the code in C. But that is a topic for another day.

-

Jesse listed indications and contraindications for using async in “What Is Async, How Does It Work, And When Should I Use It?”:. Mike Bayer compared the throughput of asyncio and multithreading for different workloads in “Asynchronous Python and Databases”:

-

For a complex solution to this problem, see http://www.tornadoweb.org/en/stable/stack_context.html

-

The @asyncio.coroutine decorator is not magical. In fact, if it decorates a generator function and the PYTHONASYNCIODEBUG environment variable is not set, the decorator does practically nothing. It just sets an attribute, _is_coroutine, for the convenience of other parts of the framework. It is possible to use asyncio with bare generators not decorated with @asyncio.coroutine at all.

-

Python 3.5’s built-in coroutines are described in PEP 492, “Coroutines with async and await syntax.”

-

This future has many deficiencies. For example, once this future is resolved, a coroutine that yields it should resume immediately instead of pausing, but with our code it does not. See asyncio’s Future class for a complete implementation.

-

In fact, this is exactly how “yield from” works in CPython. A function increments its instruction pointer before executing each statement. But after the outer generator executes “yield from”, it subtracts 1 from its instruction pointer to keep itself pinned at the “yield from” statement. Then it yields to its caller. The cycle repeats until the inner generator throws StopIteration, at which point the outer generator finally allows itself to advance to the next instruction.

-

https://docs.python.org/3/library/queue.html

-

https://docs.python.org/3/library/asyncio-sync.html

-

The actual asyncio.Queue implementation uses an asyncio.Event in place of the Future shown here. The difference is an Event can be reset, whereas a Future cannot transition from resolved back to pending.

-

https://glyph.twistedmatrix.com/2014/02/unyielding.html

-